The Construction of Space Shuttle Launch Complex 39-B

A very personal and technical written and photographic history, by James MacLaren.

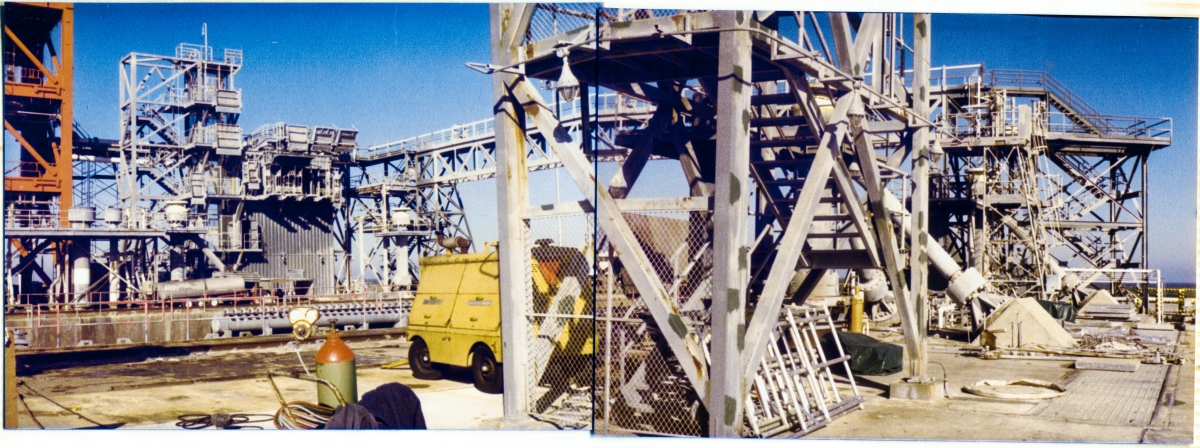

Page 41: North Pad Deck - Lingering Shadows of Apollo.

| Pad B Stories - Table of Contents |

Very well then, following the brutally-technical labyrinth I wriggled and crawled and walked and shinnied and climbed you through on Page 37, I took you up on top of the tower for a breather to enjoy the spectacular scenery looking downcoast toward Pad A, complete with a Space Shuttle sitting on top of it, and in so doing, awarded you some time off for good behavior with a well-earned respite from the technical end of things via the no-stress diversions of Page 38, Page 39, and Page 40, but now it's time to re-enter the world of actually building a launch pad, and we're going to be returning to that, and this time we're not just going to be jumping into the deep end of the pool, we're going to be swimming down to the bottom and grabbing heavy lead weights and then swimming back up to the surface with them, and we need to be in pretty good shape so we don't drown while we're doing it, so get ready for it, ok?

We're over on the east side of the Flame Trench, and we're looking across a panorama that extends from nearly due west to nearly due north, and this panorama encompasses a lot of things you've already seen from down at Pad-Deck-level and from up on the towers above, and also encompasses a lot of things you haven't seen, from anywhere, and whether you've seen it before or not, I haven't really given it the detailed treatment it requires for proper understanding, and that was because I knew this image was coming, and now that we're here, the time has come to stand with our boots on the concrete of the Pad Deck with a strong winter wind cutting though our clothing, noticeably colder than people expect for a place like Florida, right next to, and right across from, one of the most bewildering arrays of differing equipment, used for an equally bewildering array of differing purposes, and, with as detailed a photograph as I've got, work our way through it all, element by element, and in so doing gain still more insight, still more of a workman's understanding, and still more familiarity with our former Apollo Saturn V and Saturn 1B, and in-the-now nascent Space Shuttle Launch Pad.

And I guess, as a starting point, before we swim down to the bottom of the deep end and grab our first lead weight, we're going to need some kind of overview. We're going to need some kind of way to look at this stuff, technically, in a way that's not over-detailed and not overwhelming, at least not at first, so that we can kind of dip our toes in the water, just a little bit, to begin with, to maybe give ourselves a fighting chance to see what's what, and where's where, and then maybe start getting to the bottom of things for real, after that.

Unfortunately, of the three major Space Shuttle drawing packages in my possession, 79K04400 (Pad A, RSS, FSS, Pad Deck and Flame Trench), 79K10338 (Pad B, FSS, Pad Deck and Flame Trench), 79K14110 (Pad B, RSS), none of them have anything by way of a fully-encompassing vicinity view, or perspective view, or general elevation view which shows all of the things visible in our photograph, all at the same time.

And if that's not bad enough, a fair bit of what's up here is completely unchanged, leftover stuff from the Apollo Program, which means it's not going to properly show up at all on our Space Shuttle drawings, and so now I'm going to be introducing some of the old Apollo stuff in the form of the original 1960's Project Apollo engineering drawings for the Pad, done by the U.S. Army Corp of Engineers using the original A&E firm of Giffels and Rossetti, Inc., from Detroit Michigan, into this already too-large and too-detailed narrative, and some of those drawings are... shall we say... less than friendly, and leave it at that.

Sigh.

So we find ourselves at a disadvantage right from the beginning, and I'm going to do the best I can with it, but you need to know that's it's going to be a little chopped-up, and we're going to be bouncing around from drawing to drawing, more than usual, just trying to gain a generalized sense of what all this stuff is, ok?

And you also need to know that this page, all by itself, is most likely going to wind up book-length, with a very high word-count.

We're about to get into a lot of stuff.

We're about to get into a lot of stuff that's deeply-complex and ramified.

So take a deep breath, here we go.

I'll start off with the best I can do, as a general overview, showing you where you are, where you're looking, and what you can see, but it's missing things, and it's also one of the older Shuttle drawings, and as such, not everything that's shown in the drawing is correct, or even there at all, as we're seeing it in my panorama photograph.

The Apollo-era version of things (viewed from the opposite direction) looks like this, and is significantly different from what's showing in my panorama.

So now we can return to our photograph, and see things labeled with colors to indicate individual elements. Please keep in mind that the outlining and labeling on this photograph is pretty rough, and there's a lot more going on that I did not label (It's already bad enough with all this stuff, right? Why make it worse?), but for the most part, what we're about to get into with this, most of the main players, are marked up, and yes, it's still very confusing, but click on the image to make sure it's rendered at its full 4,000 pixel width, and then go slow, follow the solid and dashed colored lines, and just kind of do the best you can with it, ok?

If things still fail to make sense, do not trouble yourself over it, ok? Maybe it will come, later, when we get into the nitty-gritty of each thing, or maybe it won't, and it's ok either way.

We're just walking around the Pad, right? We're just taking a stroll on a chilly winter day, up on the Pad Deck, out at Launch Complex 39-B, ok? Nothing more than that. Just an easy walkabout through the cold sunshine beneath a cobalt Florida Sky.

We'll start with the easiest thing of all, and that's the FSS. It's giant and it's painted red, and although not much of it is visible in our photograph, it's easy enough to identify over there in the top left margin of our panorama. Also, we've already spent a fair bit of time with the FSS in these essays, and by now we're becoming pretty familiar with it.

Here it is here, in our photograph, all nice and labeled-up for you, just in case a gigantic two-hundred and fifty foot tall steel tower painted bright red might have somehow slipped your mind a little.

Easy as pie.

But now, we're going to go from easy, to.... not as easy.

Which is why we're here in the first place, right? We want to learn about this place, and we want to learn about the whole place, and after all, it is a Launch Pad, and everybody understands that rockets and launch pads are not known for their simplicity or ease-of-understanding, and everybody else who's not up for this stuff has already long-since autoselected themselves right on out of here, so it's just us now, and we can tackle this stuff on our own terms without having to worry about dumbing it down, right?

So ok.

So the Pad/MLP Utilities Interface Platform. Which we're not seeing all of, but we're seeing enough of to warrant delving into it.

And this platform, in and of itself, is about as straightforward and simple as you could ever ask for in a place like this, except that, as usual, there's a little more going on with it than might at first meet the eye.

A fair amount of our trouble with the Pad/MLP Utilities Interface Platform (and much of the rest of what's coming on this page, too) stems from the fact that it was originally Apollo equipment, built back in the 1960's and pretty much unaltered from that time, and in the days of Apollo, things were different up on the pad, not least amongst which is the fact that for Apollo, there was no "FSS", and in fact the "FSS" was sitting up on top of the Mobile Launcher as a "LUT" and everything had to be fed up into the Great Box which was the Mobile Launcher, to get it to..... anywhere at all up there, including the full vertical extent of the LUT, bottom to top.

And so they just ran all the stuff that we're finding in this area, straight up from inside of the Pad itself vertically right on through the concrete and steel of the Pad Deck, straight up into the underside of the ML with a happy little platform to work off of, in the gloom up under there, to let us manually connect and disconnect all the things that needed connecting and disconnecting every time that monstrosity of a Mobile Launcher (with or without the monstrosity of a Saturn V sitting on top of it) was trundled out to the Pad, set down on its Support Pedestals, put to whatever use it was put to, including sending people to the Moon for godsakes, and then jacked back up and returned to the VAB on the back of the Crawler, and tra la la, easy peasy, we're all good to go.

Or at least it was all good to go until they summarily decapitated the ML, cannibalized the LUT, turned it into an FSS, and then bolted it down to the Pad Deck, next to where the transmogrified ML, which had now become an MLP, sat placidly on top of the MLP Mount Mechanisms. The original Apollo construction was significantly modified for Space Shuttle, and some of the modifications are pretty sneaky, and result in alterations to things that might not be apparent, with a casual glance.

As an example of this sort of thing, consider that the FSS was a gigantic steel structure, weighing almost as much as the RSS, coming in at just under 4 million pounds, and it would definitely require additional foundation pile supports beneath it, and those piles went straight down through the pad and deep beneath the surface of the Pad Deck, carrying some seriously-thick, buried and not-so-buried, heavily steel-reinforced concrete caps and struts and pedestals, in the company of a few new tunnels, and... and anything that was preexisting, anything that was already there, and in the way, was going to have to move.

Primary Structure has the right-of-way over everything else, and for that reason, things move when Primary Structure is added to, altered, removed or whatever else might be deemed best for the most efficient construction of whatever it is you're trying to build.

And it's all pretty big stuff, and that too kind of becomes an impediment to understanding, all by itself, and...

How big was the MLP anyway?

And they give you numbers, and they give you facts, and they tell you stuff, but really.....

How big is it?

So I made a composite image for you, to try to give you an idea of how big this box is, and to do that we'll need to put our box someplace where it has something that everybody can relate to for size, to compare it with, so... how 'bout a baseball stadium?

So I slapped it in to a baseball stadium, sloppy as hell (but the scaling of the relative sizes of everything is correct), I'm no Rembrandt, and I'm sure there's a thousand and one things wrong here, but...

You're able, even with all the faults, to at least get some kind of an idea...

Just how big this thing is.

So take me out to the ball game, and bring the MLP along with me when you do.

Like so.

Phew!

Big enough, I guess.

And the Utilities Interface Platform sat up underneath this huge thing, and I didn't add it into my composite image, but if I did it would be somewhere between home plate and third base, almost all the way to third base, a little over toward the pitcher's mound some, and it kind of gets lost up under there. Kind of gets hard to see over there in the gloom underneath the MLP over there.

And, despite the fact that I have accumulated what, at this time, probably amounts to two or three thousand very-large-scale contract drawings of this stuff, I have not been able to locate a single drawing that actually tells you how to build, or modify, or deal with existing, for this platform. I have no dedicated structural rendering of this platform.

Anywhere.

In any one drawing package.

The Utilities Interface Platform, after all, held no actual significance in the larger scheme of the overall design of the Launch Pad. It was a means to an end, and the end consisted in the connection and disconnection of multiple systems, who's only common point of intersection was that they all needed to be run from down inside the pad, vertically through the concrete and steel of the Pad Deck, and then from there, up and into the Mobile Launcher, in more or less the same place. Firex did not care about Ventilation Air. Potable Water did not care about Chilled Water. And so on. They rubbed shoulders together here, and that's fine, but the overarching engineering which governed their full particulars never did, and was never intended to, interact communally with each other above and beyond staying out of each other's way and ensuring enough working space around any individual element to permit the Pad Technicians to do their individual jobs, and for that reason, with the Pad/ML Utilities Interface Platform, we find ourselves having to pick through things, one system at a time, working out the details of any given pipe or duct running up through this thing.

So I'm going to have to do the best I can, indirectly, with what I've got, and we'll be ok, but we're going to have to bounce around some, and I guess our first bounce will be the Pad Deck, to see if we can find anything maybe that this platform attaches to.

And sure enough, when we take a close look at the original Project Apollo structural drawing that shows us the Pad Deck (back then they called it a Pad Apron, but by now we're hip to those kinds of shifts in nomenclature, and we know full-well exactly what we're looking at here), we discover, exactly where our Utility Interface Platform would be located, via the callouts on the drawing. One of which specifies 1"Ø Anchor Bolts, with four inches projection (which is how far up out of the concrete they're embedded within they protrude), and the other four of which specify a spacing between each pair of anchor bolts at all four corners of where the platform goes, as being 5". Further examination (you can really learn a lot when you look close at things) reveals there to only be two anchor bolts at each corner location, and that whole deal, only a total of 8 anchor bolts, only 5" apart per pair, lets us know in no uncertain terms that whatever it is that's being attached to the Pad Deck here is nothing particularly heavy, nothing seeing any kind of high stress loads, and all of this screams, "Yes, this is where the Utilities Interface Platform goes," and it's also telling you how much space it takes up, including it's shape, and...

Guilty as charged, case closed.

Also, in our photograph, we've just entered the dreaded Zone of Structural Elements Overlap, and the Bewilderment Factor promptly takes a huge leap upwards as we find ourselves attempting to precisely locate what's what, faced with multiple overlapping lines and shapes, some of which are part of what we're interested in, and some of which are not, resulting in a confused labyrinth which refuses to give itself away to us with sufficient clarity, so in this particular instance, insofar as figuring out what the deal is, with exactly where this platform goes, we find that we can trust the drawing more than we can trust the photograph, and that's kinda nice to be able to do a thing like that, every once in a while.

So ok, so now that you know where it is, I'm going to crop down on the photograph, and highlight it again, this time in more detail.

And of course, now that we're properly zoomed in on things, we are free to make the horrified discovery that it's a mess down there, and you may rest assured that in this more-detailed image that I've highlighted, I've missed more than just a few things, and the image itself cannot possibly be showing us everything that's down here anyway (some of which was terminated with a blind flange just above the concrete surface of the Pad Deck, and couple all of that with the fact that this is an active construction area with somebody's giant diesel fuel tank (for compressors, generators, trucks, cranes, you-name-it) on a multi-wheel trailer sitting right there, and ladders, and hoses, and stuff in the background, and.....

And now we can look at another one of our drawings to see how some (but not all) of it was reworked, where we can at least see the platform itself, along with the stair you had to walk up to get on top of it, and give that a look.

They've decided to call it, blandly and unhelpfully, a "service" platform (as if there's not another thousand or so "service" platforms located all over the place on both towers, the Pad Deck, and who knows where else), but they've also given us the actual outline of the platform in plan view (barely, but it's there) which means we can now get a proper look at what's coming up though the pad deck into this platform starting underneath it in the Catacombs, if we want to identify it, and then compare it with the original Apollo drawing, which of course is how this stuff was furnished and installed, back on Day One.

This is also a teachable moment insofar as it becomes an opportunity to show you a few of the very numerous and very sneaky differences between Pads A and B, and I've marked up the corresponding Pad A drawings and will be providing you with links to them, so that you can kind of play a little bit of "Spot the Difference" with it, and give yourself a better feel for the hidden difficulties in dealing with a pair of Launch Pads that are identical twins, except that they're not. And the differences are more or less randomly sprinkled around, each of them with its own lost history of what it was that caused the change, so we wind up flying blind with this kind of stuff, feeling our way along, and we hope very much to not make some kind of serious mistake with this stuff, which could very easily cost us a bundle of money, wind up damaging something very expensive, and/or pose a very realistic threat of getting somebody hurt or killed. So go ahead and have a little no-consequence fun with it if you want, or if you want to immerse yourself in my world just a little bit deeper, in an effort to gain a greater understanding of how things work.

As far as letting you know where "The Difference" really is on this stuff? No. You're on your own with it. Just like we were. Godspeed and good luck.

And here's your first "Spot the Difference" drawing (and no, differences in my labeling and highlighting do not count as things we're looking for), showing us the exact same thing we just looked at a couple of paragraphs above (but for Pad A this time), when we were locating ourselves as regards where the Utilities Interface Platform is, and what's actually feeding up into it from inside the Catacombs, below the Pad Deck.

So, despite all the obvious and not-so-obvious pitfalls along the way, we actually can figure out what the hell we're looking at here. In the photograph, the two largest "stovepipe" looking things coming up above the deck of this platform are (left) a 42" diameter Ventilation Air Supply duct for the MLP, and (right) an 18" diameter Dehumidified Air (about which more, later, when we get to the ECS stuff farther down on this page) supply duct, also for the MLP.

The other stuff visible in the photograph is identifiable, but I'm not going to get into that level of detail with things here and now, and I'll leave it as an exercise for the student to use the reference material I've already given you to pick through it all and identify it, so here's a bit more reference material (But it's not a complete detailing of everything that's headed up into the underside of the MLP from here, ok? Never ever assume that just because something fails to show on any given drawing, or drawingS, that it's not there. All that means is that it's not on the drawing(s) you're looking at, and it's your responsibility as a contractor to have gone through the entire engineering drawings and specifications package, and to have found, on your own, every last bit of it.) for you to look at, to help you understand what's going on with this stuff here, ok?

And one of the things you're going to be identifying as you pick through this stuff is "Chilled Water", and if I don't do it right now, I'm probably never going to do it, so we're going to stop right here and address "Chilled Water" both supply and return, and find out what that's for, because on the surface of things... why? Why chilled water?

And it turns out that for institutional-size or industrial-size air conditioning systems, the business of cooling the air in some location or other is a more efficient process when it's done by cooling ambient air with Air Handler Units out at the endpoints of the system, out where the ambient-temperature ventilation air is just about to be pushed into the room it's going to be used in, instead of cooling that air back at some central location and then ducting the already-chilled air for great distances to its endpoints, or installing a whole bunch of individual air conditioners and/or Evaporators all over the place.

So they chill the water at the central location where the Chiller (which is a giant contraption, but nobody cares because it's outdoors and it's not taking up room inside your facility) lives, and then they pipe the chilled water, through insulated pipes, out to where they need it, and then they use that Chilled Water Supply to chill the ambient air in heat exchangers out at the endpoints of the system, and then they continue with the savings by sending the water right back to the centralized chiller again. Once the chilled water has done its job cooling the air in the heat exchangers out at the endpoints of the system, it's still a little coolish, and sending that coolish water in the form of Chilled Water Return back into the central chiller results in even more savings, in the form of reduced energy that's required to pull it all the way down to the temperature it needs to be reduced to to perform its job in the heat exchangers, and this lets them turn it right back around once again in a closed-loop system, and send it right back out there to the endpoint heat exchangers once again, as Chilled Water Supply.

It might sound clumsy and complicated and inefficient (and maybe even a great way to spring a leak, too), but when you actually start building things at industrial size, it turns out that it's much cheaper and easier and more efficient to do it this way, so that's how they do it, and now you know why... CWS and CWR.

Out here, at the Pad, there are additional complications owing to (in addition to many other things) the fact that the MLP is built like a submarine, sealed up drum-tight, and the immediate area around it holds the potential for serious problems with air contamination from no end of exotic and life-threatening things, so instead of just grabbing ambient air from the immediate vicinity with a simple-enough intake fan, and then pushing it through a heat exchanger for interior air conditioning (and continued maintenance of happily-livable oxygen levels, too), they very wisely decided to locate the source of their ambient air way the hell out away from everything else, over near the Pad Perimeter, at what was called the "Remote Air Intake Facility," and from there, it was sucked into the Pad through a quite-long buried concrete tunnel that also doubled as an emergency egress escape route that could be reached by going through a short corridor extending out of the Rubber Room which was buried deep within the Pad, and there's no end of stories about that thing too, but enough already, let us not launch off into yet another ten-thousand word digression right now, ok?

Now, where were we?

Oh yeah, the Utilities Interface Platform.

Viewed from off of the Pad, this photograph shows the Utilities Interface Platform doing its job underneath the ML, which is sitting in the launch position at the Pad carrying the Apollo 8 stack.

You're looking at the Saturn V which sent the crew of Apollo 8 to lunar orbit and back, sitting atop its Mobile Launcher, which itself is sitting atop the "Launcher Umbilical Tower Support Pedestals" (which nomenclature is taken directly from the Apollo as-built drawings in my possession), with the "Arming Tower" (again, nomenclature taken directly from the as-builts, although I will continue to refer to it as the "MSS" or "Mobile Service Structure" which is what I'm used to calling it), carried on the back of the Crawler, up on the Pad Deck (which the Apollo drawings refer to as the "Apron" and which, again, I'm going to continue to refer to it with the usage I'm familiar with as "Pad Deck."), closing in on its own final destination sitting atop its own "Arming Tower Support Pedestals" but it's not quite there just yet.

Here's the same photograph of Apollo 8 highlighted with a label underneath it, and our Utilities Interface Platform is nicely visible, and you can easily see the distinctive pair of big vertical pipes for Dehumidified Air and Vent Air coming up through it to the underside of the ML, and also the stair you'd take to get up on top of it, although the very northernmost end of the platform is obscured by that white semi-trailer that's parked up on the Pad Deck.

And we've already discussed how radically things on the Pad got altered between Apollo and Space Shuttle.

So anyway, what wound up happening is that an awful lot of what once just went straight up into the underside of the Big Steel Box back in the 1960's, is now cut and rerouted sideways over to the FSS, where it can then happily continue on with its vertical runs to wherever it's needed.

And down on the Pad Deck, beneath the Utilities Interface Platform, a LOT of what once sprouted from the concrete, still sprouts from the concrete, but it then takes any number of crooked whoop-de-doo's on its way over to the FSS, and that's what you're seeing down there.

And of course some of it was terminated or removed. And maybe a new thing or two was added, and...

And us structural people never liked this stuff anyway, because as far as we were concerned, it was a bunch of weeds growing on our structure, and if we'd had our way about it, we'd have gotten out the weed-whacker and cleaned the place up nice and good.

But they didn't allow us to do such things, and we just grumbled along with it, and tried not to knock our heads on any of it whenever we were forced into close-quarters with it as part of whatever we might have been doing at the time.

So the poor Utilities Interface Platform never got any respect from me, or anybody else in the structural world, and that makes me an idiot, because, as with the 9099 Building, here I am all these years later, trying to explain this stuff, and I'm too stupid to do it.

But I'm working on it. I'm trying. And who knows? Maybe we'll get there, despite my shortcomings and inadequacies.

So that's what's going on with this thing, ok?

Alright then, what's next?

And we seem to have started off working from left to right, in our panorama, so I guess we'll let that be the path of our walkabout.

And on this walkabout, the next significant object would be the West MLP Access Stair Tower, so let's go with that, ok?

More Apollo equipment.

Unaltered.

More stuff that was originally put in place by von Braun and Crew.

More stuff with which, in addition to construction, we also get history, which of course we will need to understand first, before we can understand the construction.

And I immediately find myself learning that, despite the fact that I had lived and breathed with this thing as the West MLP Access Stair Tower (being of course, on the job, much more often called, and lumped in with, "9099 Building" as was everything else over here), or sometimes just the "West Stair Tower", its actual name was "Stair 2."

But don't we already have a "Stair 2"?

Yes indeed, yes we do, already have, Stair number 2.

But that one is over on the RSS. And we've already seen it. And we've seen it from more than one point of view, too.

But the one we're dealing with now was here first, whether the people who designed the RSS were aware of it or not (which I'm quite certain they were, but the naming duplication over on the RSS was deemed acceptable anyway, by whoever or whatever might have been in charge of such things), and with or without an RSS entering into the overall picture of the Pad, this Stair 2 retained its name, unchanged.

Which stands as yet another example of the hidden trickiness of this stuff, in the form of how things get named, and how things remain named, sometimes with respect to one another, but sometimes not.

And you just have to be aware, at all times, and can never take anything for granted, no matter how mundane or trivial it might appear at first glance.

There are pitfalls. There are hidden pitfalls.

All over the place.

So ok, so Stair 2.

Which, being original Apollo equipment, and which also, is kind of lumped in with all of that messy "9099 Building" stuff, and which shows up repeatedly on the Apollo as-builts, and which, whether you know it or not, you've already seen on the drawing that gave us the callout and locations for the Utilities Interface Platform anchor bolts...

We may as well familiarize ourselves with those Apollo drawings which show this stuff, and which also kind of lump it all together, too.

We'll start off with the Pad Deck (which the Apollo drawings will be calling the "Apron" as we already know).

And here's the whole "lump" including the ECS Tower, the "9099 Building" (which, together, on the drawing, are called out as "ECS and I/C Pad Tower", Stair 2, and Elevator 2 (called out as "Stair & Elevator #2"). All cheek-by-jowl. All, visually anyway, one thing. One big contrapted steel... thing. And I've dropped in the location of the Apollo-era as-yet-unimagined FSS in an effort to help you visualize this whole area on these Apollo drawings, in terms of the Space Shuttle drawings and photographs you've already seen, and are already familiar with to one degree or another. North is to the left, on this drawing, ok? And just for laughs, here's the Pad A version of the same drawing, so you can play "Spot the Difference" some more, finding the disagreements between the two pads.

Here you're seeing just the "9099" part of things with Stair 2 highlighted, zoomed in, in a series of plan views, from the Pad Deck at elevation 53'-0", and going up from there. And on this drawing, north is no longer to the left, but is now toward the top of the drawing, so be sure and keep that in mind, too, if you're looking at this drawing immediately after looking at the drawing I just referred to, in the paragraph above this one.

Stair 2 lives inside of a robust tube-steel structural framework that also serves to strengthen and stiffen the elevator framing right next to it (we'll get to that too, so hang on, ok?), and the stair is easily-enough identifiable as a stair tower on the panorama photograph in its upper reaches, but then, as you descend toward the Pad Deck, it begins to become confusingly engaged with the tangled dark silhouettes of the ECS Support Steel and Catwalk framing behind it, and then, dropping lower, first the MLP Mount Mechanism in front of it (the top of which looks confusingly similar to the Vent and Dehumidified Air "Stovepipes" on top of the Utilities Interface Platform just to the left of it), and then our Utilities Interface Platform which is also in front of it, and then down at the very bottom, the big diesel tank and other construction gear which is more or less sitting on the Pad Deck, and the overall effect is to make the precise location of all the elements of just the stair itself (stair stringers, handrails, landings, structural framing) impossible to properly, completely, and accurately sort out from all the rest of that stuff.

It's a complete mess over here, and none of this stuff gives itself away easily or willingly, so try not to be too hard on yourself if you're having trouble (or are even completely unable) making useful sense out of it, visually.

Here's Stair 2 here, on the Apollo concrete foundations drawing, which lets us see that things did not stop at the surface of the concrete, but kept right on going, down into the body of the Pad itself.

And here it is again, just the main structural framing for it (quite sturdy stuff), in elevation views showing the whole "9099" framework, looking east (from "behind" it) and looking west (the view we're getting in the panorama at the top of this page).

And just as a wee little hint of foreshadowing, I'm going to let you know there are problems with this drawing (and other drawings which show us this area too), but I'm not going to go any further with it than that, right now, but later on...

...oh yes, much much further down the rabbit hole shall we go.

Stair 2 is yet another emergency egress stair, and its original Apollo-era primary job was to provide an escape route off of the Mobile Launcher over on the west side in time of need, which I do not know if it ever got used for, even once. When we were converting the pad for Space Shuttle, there was never an MLP parked over the Flame Trench, and nobody ever used this stair. For anything. Including me. It didn't really "go" anywhere. It afforded no spectacular views of... anything, really. It was ugly. And it lived in an ugly neighborhood. Over in that whole blighted "9099" mess. And so it languished over there, alone, unloved, uncared-for. While the world spun madly along without it.

And right next to Stair 2, butt up against it, to the point of sharing one whole structural side with it, the elevator that I never even suspected as existing, the whole time I was out there. Five full years. Never suspicioned the least of it.

Elevator Number 2.

And that "Number 2" being in italics is because there was an Elevator Number 1, which I only just now, as part of researching this stuff, learned the existence of.

We'll get to more about that, later on here.

For now, we still have Elevator Number 2 to deal with.

"Don't look like any kind of elevator I've ever seen."

Which might help to explain why I never even suspected that it even was an elevator in the first place.

Old-timey-looking kind of deal.

And it was a hydraulic elevator, which means there was no "elevator machinery room" up on top of it.

No hoists. No wire rope. No metal siding to enclose it all and keep the weather off of it. None of the lifting gear that people just sort of automatically assume comes with an elevator. Any elevator.

Hydraulic elevators work like some of the lifts you see in auto mechanic shops, with a sort of tube or column that comes up out of the ground underneath them, and pushes them, from below, instead of having wire ropes that are pulling them, from above.

And the elevator "shaft" is no such thing, either.

No walls. No enclosure. Just some steel framing "covered over" with expanded metal screen, or some other kind of wide-open steel fabric or "chain link fencing" kind of stuff.

Which the breeze wafts right on through, unimpeded, and which is also very much "see-through."

And the elevator cab itself completes the picture by also not being solidly enclosed. More of the same kind of open construction that you got with the elevator shaft.

Even the doors are see-through. And it had a pair of these "scissor gate" doors, one on the front and one on the back, which of course could be opened, from inside the elevator cab, in either direction, on either side, "front" or "back."

Along its front side, which you're seeing in the photograph and which faced east toward the MLP, three levels of counterweighted flip-up platforms which always stayed locked in the "up" position, further camouflaged it. Elevators and flip-ups just don't really seem to go together. Or at least in my mind they don't go together.

So... if you encounter one of these things. And if you were not expecting to be encountering an elevator, and then you find yourself encountering it buried deeply within a large surrounding snarl of disjointed-looking steel members and mystery-equipment which is all going every whichaway all over the place without apparent rhyme or reason...

...well then... perhaps we'll forgive you for failing to realize you're even dealing with an elevator in the first place.

But this elevator, Elevator 2, is no slouch. No lightweight item. No trivial thing.

This elevator is the real deal.

This elevator is how the astronauts of Apollo, traveled between the Pad Deck and the Mobile Launcher, and thence to their Apollo Capsule and back. Or at least when they weren't coming back, the long way around, by way of the Moon.

And right here, we need to re-examine the depth of my own stupidity in failing to even realize there was an elevator here in the first place.

I mean, come on, how did you expect people to get inside of the rockets they were riding, hmm?

Did you think they just sort of float on up there?

And in my own woeful defense of the profundity of my own astounding lack of awareness with this stuff, I can offer only the fact that, when I first showed up out here, there was already a great big FSS sitting right there, and for my own (very limited) understanding at the time, access to the MLP would be gained by taking one of the two FSS elevators, from the Pad Deck, up to level 80'-0" or 100'-0", exiting the elevator (but not the elevator over in that mess of 9099 Building crap) and walking over to the east side of the FSS, and then stepping lightly across the flip-down platforms that lived over there, either into (through a door in the side), or onto (out on to the top deckplates) the MLP.

When the time came for me to actually start walking around on the MLP, that was invariably done over at Pad A, and by that time Pad A had become active, and if there was an MLP spanning the Flame Trench over there, it was because there was a Space Shuttle sitting on top of it, and we almost always walked down RSS Stair 1 or Stair 2 from the undercarriage of the main body of the RSS to get there.

And it was sheer repetition. Sheer unthinking habit. And it completely blinded me to the fact that there was no FSS back when Apollo was flying, and what the implications of a thing like that might really be.

Which makes me guilty as charged. Guilty of being stupider than a box of rocks.

I throw myself upon the mercy of the court.

And I use my own unbelievable stupidity as a cautionary tale.

Just because you're whip-smart here...

...does not mean you're not box-of-rocks-stupid...

...there.

Back-checking. Cross-checking. Fact-checking. Self-checking.

There can never be enough of it.

Because if there was, we wouldn't be constantly finding more examples.

Examples of our own fallibility. Our own feet of clay. Our own stunning lacks and wants.

And the same goes for all the world around us, and in particular, it goes double, no... triple, for all things and all people which we believe to be possessed of The Truth.

So mind your "authority figures" ok?

Especially the ones you believe in.

You already know the "other guys" are beyond redemption.

But what about your guys?

Trust them not, for they are deeply fallible and venal, too.

And about those flip-up platforms on Elevator 2...

They do not look like the sorts of flip-ups we're used to dealing with.

Even the flip-ups over here are somehow... uglier, too.

They're definitely not as "neat" or "clean" looking. They have a sort of messy look about them and I can only presume that they look that way because they're all counterweighted, in addition to being covered with solid sheets of checkerplate instead of the steel-bar grating we've gotten used to seeing all over the RSS.

There are three of them associated with Elevator 2, at elevation 75'-11", 89'-7", and 99'-6", and in our photograph at the top of this page, you can see them in their "retracted" positions, locked in place, pivoted back, with their bottom sides showing.

All three of them are a little different, and here they are on the structural drawing.

And here they are (and some others, too), in detail view, showing not only how the counterweights were sort of underslung, behind the hinge, but that they had pretty nice bearings in them, too.

Over on the RSS, whether or not it was because there was almost never enough room beneath flip-up platforms to permit the additional space envelope taken up by the counterweights, or that there was almost always enough room up above them combined with sturdy structural support, for whatever lifting gear might be needed to lift the heavy platforms up and down, or perhaps something else, the whole design philosophy of flip-up platforming changed, and counterweights were dispensed with and not used. But out here, in the "9099" area, counterweighted flip-platforms are the norm. I do not know why things changed, but the change is clearly visible with these things, and the only place I'm aware of which continued with the use of counterweighted flip-ups is on the side of the FSS that faced the MLP at elevations 80'-0" and 100'-0" (which we did a little work on, and is another one of those places where the ironworkers let me "play" with an arc-welder) and whether or not it had something to do with providing access to the MLP is another question I cannot answer.

These flip-ups provided the exact same access for the Space Shuttle's MLP as they did for Apollo's ML, two levels inside, and one level on top.

And with the counterweights, they required much less effort and caution to raise and lower into position. No winches, no hoists, no hooks, no gear.

Elevator 2 was the "ground" end of a larger system which reached all the way to the hatch on the Apollo Command Module, sitting on top of the Saturn V which propelled it to the Moon and back.

This elevator provided access to the Mobile Launcher Deck, but the preferred access into the elevators on the LUT was via interior Deck 'A' on the Mobile Launcher, which provided enclosed, weather-protected access to those LUT Elevators (which sat one-behind-the-other facing the Saturn V, as opposed to how the elevators in the FSS sat side-by-side facing the RSS), and while we're here, I never could figure out how they came up with the daffy naming system they had for the different levels of the Mobile Launcher, which goes (from the top down, which is already a little "off" to my way of thinking) Deck '0' (that's a zero, not the letter 'O') which is the top deckplates of the ML, sitting beneath the sky, down one level to Deck 'A' which is the mid-level deck, and then down one more level to Deck 'B' which is the bottom level, the lowest steel plates of the "box" itself.

So. From the top down: "Deck 0, Deck A, Deck B."

"Uh... ok. Ok... sure. Sure thing. Whatever you say."

And so did they say.

Here's a drawing of all this stuff in its original Apollo configuration that shows you how the whole thing fits together, as a sort of inset over on the right side of the drawing, with everything set up in "Run for your lives!" emergency egress configuration.

And of course by now, you're probably saying to yourself, "Ye gods, this is waaay more about Elevator 2 than I ever wanted to know, surely we're done with it, right?"

Nope.

Not yet.

Not quite.

There's the small matter of the "Camera Platform" that lived on top of it.

Which Camera Platform, in days of yore, when Apollo was still flying, came complete with a jib crane up on top of it, too.

And really, this Camera Platform is actually a part of Stair 2, but c'mon man, give it a rest. Let it go. There's no need to get completely psychotic about pointlessly-rigid adherence to nit-picky stuff like that, but, in truth, this platform could not be gotten to via Elevator 2, and instead was reached from the upper landing on Stair 2, by climbing a ladder which took you to the ¼" steel checkerplate that defines this platform, which just happens to share the envelope of Elevator 2, by sitting directly on top of it, using its structural framework as its own.

But it's not really any part of Elevator 2, no matter what it might look like, ok?

And by the time I showed up, the Jib Crane was already gone, but since we're here, and since we're doing a little history with this stuff, we may as well dig all the way down to the bottom of things, right?

So let us continue to use our old Apollo drawings, and get oriented, and see about our little Camera Platform and (no longer existent) Jib Crane.

And here it is here, on one of the Apollo architectural drawings, A-311A, with a pair of elevation views that show us the whole "9099" schmutz, viewed from the west as a section cut, taken vertically along the western perimeter of the elevator and stair structural framing, looking east (which is the opposite direction we're viewing this stuff from in our panorama photograph at the top of this page), and also viewed from the north as a section cut also taken vertically, right down the centerline of the structural framing that is shared between elevator and stair, to the exclusion of the elevator, looking south, which means that only the stair is visible, and not the elevator. Both views are simple enough to deal with conceptually, now that we're starting to get into this stuff, without being too simple, and are both quite instructive for this whole area.

Among other interesting features that are visible in this drawing, is a pretty good rendering of the concrete elevator machine room immediately south of Stair 2, which housed the hydraulic machinery for Elevator 2. When I was out there, Elevator 2 was no longer used (hell, I didn't even know it was there, and without an MLP sitting over the Flame Trench, it had nowhere to even go, anyway, and I'm pretty sure by then that they'd already removed the actual elevator cab itself, and who knows, maybe even all the hydraulic equipment from the machine room, too) and they left the hoistway framework for it in place because it was less disruptive, cheaper, and easier to do so, and also because they still needed Stair 2 for emergency egress purposes, and the south face of Elevator 2 was an integral part of Stair 2, providing it with the structural integrity that it required, and so they just sort of abandoned the Elevator 2 part of things, in-place.

Here's the Jib Crane that sat over near the north side of the Camera Platform, itself, in detail view.

And here it is again, in plan view, showing the 4'-4" hook radius it had. I do not know what they originally used it for, but since there's no permanent "camera" or camera mount showing anywhere up on top of the Camera Platform, I can only presume the Jib was for lifting that stuff up here, and then taking it back down again, later on. This area is sitting up above everything else around it in a very exposed position, quite close to a departing Saturn V, and I would imagine they did not want to expose this particular photography gear to any of that, but in truth, I do not actually know.

Here's another elevation-view section cut of this area, on Apollo drawing A-313, and this one's cut along the structure on the north side of the elevator, looking south, giving you a pretty good look at the hoistway with the elevator cab inside of it down at the bottom, as well as showing you the platforms that hang off of its east side, which are visible in my panorama photograph. To the right of that section cut, we're getting another elevation-view section cut, which is an external elevation-view look at the east face of that which lives immediately north of the elevator, which is also visible in my panorama, which they're calling the "E.C.S. And I/C Pad Tower." The "I/C Pad Tower" is what we know of as the actual 9099 Building itself, which also includes the ECS (Environmental Control System, in case you've forgotten) part of things which lives directly on top of the 9099 Building.

And if that's not loopy enough for you, well ok, whatta ya say we play a little more "Spot the Difference" and go have a look at this same drawing, except that it's the version for Pad A. Here you go, all nice and marked up with the Elevator 2 Hoistway like the one I showed for Pad B just now. Notice the crazy-quilt pattern of changes on this pair of drawings, which now extends beyond the stuff included in the drawing and has spread, like a some kind of dread disease, to the actual drawing number itself! Dig around in there, looking for stuff. I'm sure you have loads of fun with it. And we're not done with this kind of stuff yet, either. It gets better. Stick around. Wait till you see what's coming.

For now, it's enough to know that from here on over, for everything north of elevator 2, things were significantly modified after they were originally constructed as depicted on our as-builts. We will delve into this first round of Apollo-era modifications a little bit later on, ok?

And of course, following that initial set of Apollo alterations, things were again modified, for the Space Shuttle.

This means our set of old Apollo as-built drawings is showing us a lot of stuff that no longer existed on Pad A by the time they started flying crewed missions with Apollo 8, or on Pad B by the time they started flying crewed missions with Apollo 10, and the changed stuff was then further changed by the time I came wandering along with my camera, taking pictures of things that I had no understanding of at the time.

We're working our way north, farther and farther away from the FSS, in our panorama photograph, and we're just about to lurch off into some really deep weeds.

It's just about to get hairy, so brace yourself for it, ok?

Maybe stop here, put this thing away for a while, and go get yourself a cold one. Or two. And then come back tomorrow some time, ok?

We're going in.

The 9099 Building.

And here it is again, cropped-in on some, taken from the original high-resolution scan (which is a whopping-big 307 megabyte .tif file), exported as a 22 megabyte jpg image, in the hopes that enough of the fine detail in this ogre will come through to permit me to sufficiently explain what, in the name of all holy hell, it is that we're looking at here, and yeah, that's pretty blurry because I overscanned the original photograph taken from the photo album, and yeah, it's tough on your eyes, but yeah, there's one hell of a lot going on here, and we're just going to have to do the best we can with it, ok?

So now...

Where the hell do I even begin with this thing...?

Maybe we'll back up a little, and tell you what it's supposed to do, first (keeping in mind that, as with just about everything else out here, it has no single purpose, and instead gets used in more than one way, for more than one reason, and also keeping in mind... history).

As originally designed and built, the whole Saturn V system consisted in a rocket that was assembled and completely checked-out, inside the VAB (which originally stood for Vertical Assembly Building, and that "Vertical" part tells us they put it together standing upright from the beginning, instead of putting it together laying down, on its side, and then lifting it into an upright position after that), and then, once all the hard work had been done assembling the rocket, it got rolled out to the launch pad on a Mobile Launcher, which had a fairly simple job (in concept, anyway) of merely being a thing that the rocket sat on top of, which could be rolled the requisite distance away from its assembly building to keep from blowing that assembly building to hell, should something catastrophic occur with the partially or fully fueled rocket as part of countdown dress-rehearsals or on launch day.

In those days, "something catastrophic" was an all-too-real possibility, and everyone who worked with this stuff had either seen things go badly wrong, on or very near the ground, with their own eyes (my own parents included), or had seen pictures and movies of this kind of thing, and were therefore, extremely cautious about the whole enterprise, and the larger the rocket, the more catastrophic things would be if they went wrong, and the Saturn V was by far, the largest rocket that the Americans who built and flew it had ever dealt with, which meant that they weren't taking any chances with it, and put the rocket's launch pad far far away from the rocket's assembly building.

So.

Big box, with a tall tower, carried on the back of a specialty vehicle, which they could place their rocket on top of and roll it far far away from where it had been assembled, in order to launch it.

Which means the box and the tower on top of it, had the job of doing final preparations to launch the rocket, but not much else, other than that.

And it kind of looked like this, as it departed its assembly building for the distant launch pad.

And once the whole thing was safely out on the pad, it had to be kept "alive" and the process of keeping it alive involved supplying it with all of the gas, liquid, solid (people are solids, aren't they?) and electrical hookups it might be needing at any step along the way, prior to its departure, at which point it was strictly on its own.

And so the launch pad was furnished with all of the gas, liquid, solid, and electrical hookups, which were required, and which were hooked up, and among all of that bewildering array of different things, for Saturn V, they divided the electrical part of things into two major divisions, which were power, and instrumentation/control.

And as originally designed and built, electrical power was fed into the stack and the box it sat on top of, from one place, and electrical instrumentation/control was fed likewise into the stack and the box it sat on top of, from another place, and that "another place" is our present nemesis, the good old 9099 Building.

The whole electrical end of things can be found in the Electrical Reference Handbook, Launch Equipment Branch, Electrical Support Equipment, LC-39 which is a 296 page document containing all kinds of cool stuff, and I recommend you skim through it for content, because you just might find some really interesting stuff in there and want to dig into it deeper, and this thing has plenty of depth to dig into.

Reading in our Handbook, we find that "9099" turns out to be a very specific subset of a group of "Electrical Reference Designation Numbers" which apply to electrical systems from one end of Launch Complex 39 to the other. From the VAB to the top of the LUT, and all points in between.

In this way, using their system of Electrical Reference Designation Numbers, they were able to keep track of a HUGE number of different electrical systems and components, down to the finest degree of detail that might ever be required.

You have to go almost all the way to the very end of the Handbook to find Figure 6-7, and in Figure 6-7 you're shown a simplified breakdown of the Reference Designation Numbers, including a level-by-level rendering of the Numbers as they apply to electrical systems on the LUT, and down toward the bottom of the list, we see that the block of Reference Designation Numbers running from 9000 to 9099 falls under the heading "Mobile Launcher Term. Dist." and I would presume that "Term. Dist." would mean Terminal Distributors, just like it does for the next three line items below it, one each for LCC (Launch Control Center) VAB (Vertical Assembly Building) PTCR (Pad Terminal Connection Room), and we are now closing in on what, exactly, "9099" is actually referring to when we talk about the 9099 Building.

The section of the handbook which contains Figure 6-7 down at its bottom, gets into some pretty good detail, and here's that whole section for you to give a look, and the information we're interested in, where they tell us what, exactly, "9099" is referring to, can be found at the bottom of this page, and we see that it refers to "PTCR-LUT Instr & Control Interface" which is the place where all of the instrumentation and control wiring (which is everything except power), for everything in and on the Mobile Launcher, including the Saturn V, gets hooked up.

So it's a significant thing.

Without a 9099 Interface, the entire Box, Tower, and Rocket, all goes brain dead and enters a profound coma through which no stimulus or communication can enter or leave, and of course, that's not a good thing, is it?

So ok. So 9099.

Ok.

Got all that?

Good.

Now you can go right ahead and ignore a lot of what you just read, because for Space Shuttle, everything got reconsidered, redesigned, and rebuilt, and a LOT of it was rebuilt significantly different from the way it was originally put together for Apollo.

With a FIXED Service Structure that had an equally-permanent ROTATING Service Structure physically attached to it like a Siamese twin (but they're fraternal twins, so they're different), an awful lot of what at one time for Apollo needed to be fed upwards into the Mobile Launcher through the Power Pedestal and the 9099 Interface, was now being fed upwards, straight up out of the body of the Pad, into the FSS (and we've already met some of this stuff for the electrical end of things), and from there it fed the FSS itself, and out into the swing-arms located on the FSS, and some of it jumped across to the MLP down at the 80' elevation of the FSS, and some of it went across to the RSS, and all the systems over there, and it became possible for them to hardwire all of that stuff directly, straight up out of the guts of the launch pad, and all of a sudden, the requirements for a significant number of things needing interfaces where they could be connected, and then disconnected to and from The Box suddenly disappeared.

But certainly not everything, and among that which continued with a need for a proper connect/disconnect interface to the MLP was electrical instrumentation and control, and it constitutes a sort of nervous system for keeping our rocket, and the box it lives on top of, alive, and alert, right up to the moment of departure.

And with the addition of an FSS on the Pad Deck, coupled with a reduced need for power to be fed directly into The Box, and The Tower that sat on top of it, they determined that they could just completely eliminate the need for a separate structure for one whole side of the electrical end of things, and the structure they eliminated was the Power Pedestal, and whatever power requirements as remained which required interfacing with the box (which is no small thing on its own, with or without a LUT sitting on top of it, and it's very definitely still going to be needing plenty of power, even without the LUT), were moved over to the FSS and dealt with in that manner.

Here's the original Apollo Power Pedestal here, with Apollo 4 sitting on the pad, prior to the first-ever launch of a Saturn V. Before anybody knew if any of this stuff was even going to work or not when they fired it all up for the first time. The Power Pedestal sits over on the west side of the Mobile Launcher (same side as the 9099 Building), right next to its southwest corner as it's sitting on the Pad, and it doesn't look like much with all that gargantuan Apollo hardware next to it, but it was a fairly substantial item in its own right.

Here's the Power Pedestal on the Apollo structural drawing, and you can see that it's four stories tall, and it's made out of the same kind of quite-sturdy tube-steel framing that all of that stuff over by Stair 2 and Elevator 2 is made out of, and perhaps you're noticing a bit of familial resemblance to that stuff too.

And just so you can get a better feel for it, here it is on the electrical drawing, and on this sheet, you can start to see how this thing bears more than just a passing resemblance to our 9099 Building in regards to its upper, business, end, and how that ties across and interfaces with the Mobile Launcher. In certain ways, it's like a sort of miniature 9099 Building on its own, kind of up on stilts, and it has similar interface configurations (but not as many of them), and if you go back and look at it on the big layout drawing of the whole Pad Deck, including where I pasted in the location of where the FSS actually wound up being constructed, you can can clearly see that this thing is sitting directly in the way of where the FSS was going to be sitting, which means that we can completely eliminate it, and very easily substitute a portion of the FSS for it, saving time and money by altering existing things as much as we can, for Space Shuttle.

The place on the FSS where MLP Power wound up coming from is just out of view to the left on our photograph at the top of this page, down at elevation 80'-0" near the southeast corner of the FSS, and we're not going to get into it any further at this point, but at least this way you now know what's going on with the MLP Power end of things.

And now that we've very gently dipped our toe into this dark and mysterious water, perhaps at this point we can go back to the 9099 Building itself, and see what's going on with it as it's showing in my photograph at the top of this page.

Let's review.

Here's the 9099 Building once again, more or less by itself.

But this image is still too busy, too messy, and there's still way too much going on in it.

So we're going to close in on it some, but not all the way, ok?

So now we crop in a little more, but not all the way. Not all the way to the exclusion of some of the stuff that surrounds it. In this view, we're still seeing some of Elevator 2 on the left side of the 9099 Building, and some of the LOX Tower on its right side. So it's still a little messy, but since the stuff on either side of it is in fact an integral part of the whole set of steel structures over here, firmly integrated with, and connected to, the 9099 Building to its left, to its right, and on top of it too, we'll leave this "extra" stuff in there for now, ok?

And from here, we can finally hone in on some of the discrete parts of the 9099 Building that we need to find out about if we're ever going to get to the point where we actually understand our photograph of it.

And for our first visit to some of the discreet parts of the 9099 Building, we may as well go right to the heart of the matter, and take a look at the business end of things, and that would be the "Dolly Area" which is where the Dollys that can be rolled outward from their safe enclosure within the blast-protected confines of the 9099 Building are located.

There are four Dollys.

When they are extended, rolled forward, toward the MLP, from their stowed positions, they carry a LOT of electrical cables with them out close to the side of the MLP.

From there, somebody has to use short "patch" cables to manually connect every single one of these numerous cables, a lot of which extend in one form or another, away from the back side of the Dolly, 4 miles all the way back to the Launch Control Center at the VAB (and we'll be seeing those patch-cables pretty soon, ok?), on all four Dollys, to their matching connection points on the MLP.

MLP electrical instrumentation/control. Allofit.

Electrical instrumentation/control for the MLP (The Box) itself, and also for the free-standing Space Shuttle sitting on top of the box, after the RSS has been rotated back and away from it, when it's poised for launch.

And there's a LOT going on with this stuff.

An ASTOUNDING amount, in fact.

The area you just saw labeled on the photograph can be seen highlighted on the original Apollo drawing, and the part that's highlighted on the drawing has in no way been sensibly modified from its original Apollo configuration as you see it in the photograph. For just the Dolly Area, its all the same stuff, ok?

Here it is again on another Apollo drawing, this time in plan view, and I've highlighted the area at elevation 77'-11" which is where the Dollys live, and in this plan view you can see that this thing is a little tricky (and of course the drawing is none-too-comprehensible for people who aren't familiar with this kind of stuff, so I'm going to highlight where the Mobile Launcher will be sitting at this elevation when its parked over the Flame Trench, and add it in so you can get a somewhat better look at how everybody all works together in this area), and there's a piece of the siding-enclosed portion of things over on the north end of the Dolly Area that's not visible in the photograph because it's kind of stepped back, away from the MLP, but the unenclosed narrow finger-like flip-up platform that fronts this stepped-back area (the northernmost flip-up) is, itself, not stepped back, leaving it clearly visible in the photograph, and it's also, in the photograph, the only flip-up that's not in a lowered position, and instead is standing upright. Rowr!

Ok. I think you've got enough now, to allow you to make sense of the Apollo drawing which shows the Dollys in detail, inside of the 9099 Building, extending out toward the MLP/ML/LUT/Whateverthehellthey'recallingit, in "profile" view, from the side. Notice please, that in the part where I've highlighted things with color, our Flip-up Platforms are not shown. Not there. Or at least on this part of this drawing they're not there. But they're there, ok? Rely on it.

I have specifically faded out the "face on" elevation view of the 9099 Building, as well as the three separate plan views of it, in an attempt to avoid as much confusion as I can, at this early state of explaining this thing.

For now, it's far more than enough to just try and absorb this monstrosity bare-bones, without making things any worse than they already are.

But now we need to tiptoe just a bit farther into it, and we'll do that by showing you the drawing you just looked at, but this time with some of the faded-out area restored, in the form of a plan view of the elevation 77'-11" Dolly Area which I've added the flip-ups into (they're not there in the Pad B original) and the enclosed area labeled.

The ML/LUT/MLP (Don't you just love how they were constantly changing the names of stuff all the time?) sat on its Support Pedestals quite close to the 9099 Building, and it had to be that way, in order to minimize the gap between the two very substantial objects, so as the technicians could reach across the gap with the Patch Cables (which are heavy, even when they're short, and every little bit of additional space in between the 9099 Building and the MLP meant that every one of those Patch Cables was that much longer, and that much heavier, and that much more difficult and potentially dangerous to work with) with a reasonable expectation of even being able to get the work done at all.

Now I'm going to show you that same drawing without having anything faded out. Our Pad B version of the drawing has the two elevation views unpleasantly cramped in there side-by-side together, and that was forced on them by the changes that had to be done somewhere along the line, and the differences (we're still playing Spot the Difference, remember?) between the original Pad A (five feet lower than B, mind the elevations, ok?) version of the Drawing and the Pad B Drawing are significant, and we're going to find ourselves veering off into some pretty wild and woolly territory with that end of things, but not now, ok? But in preparation for what's coming, and since we're already here, and since we're already playing Spot the Difference, please notice how what, at Pad A was once the "LUT Instrumentation Interface Pedestal" has become, at Pad B, the "ECS & I/C Pad Tower" down there in the drawing title block. Hmm hmm hmm...

But please, not now, ok? Pretty please?

It gets hairy out there.

We've already got our hands full with what we're dealing with right now, thank you very much.

In addition to the Dollys themselves on the drawing, you're also seeing the cables connected to the MLP, and in the smaller plan view over on the right side of the drawing, the 77'-11" Landing Area, you're seeing the finger-like flip-up platforms that are located on both sides of all four Dollys (making for five flip-ups in total), flipped-up, in their "standing" retracted positions.

The flip-ups were mandatory, because without them, the techs who were hooking up the cables would have nothing to stand on, twenty-five feet above the concrete of the Pad Deck down there below them, and that's not gonna work, so... finger flip-ups, and it's "finger" flip-ups because despite the fact that this whole Launch Pad is beyond gigantic, there so much stuff all crammed in here cheek-by-jowl, that there's hardly any room for any of it! The amount of stuff in here, the amount of wildly-different stuff in here, crammed in like sardines in a can, simply beggars the imagination, and your brain completely fails to register any of that end of things. Until you start digging down into the the particulars of any given item or system, at which point your brain does register, and promptly bails out on you as a result, leaving you stranded, trying to figure this shit out, and...

...it's not easy, ok?

So hang in there, ok? Slow down. Give it time. Give it consideration. It'll come, but it won't come easy.

Zoom in on that drawing, nice and close, and give that whole Dolly mechanism shown in "profile" view up in the top left, the detailed looking-at which it is so eminently worthy of.

Quite the contraption, eh?

And now that we're this deep, why not? Why not go all the way to the bottom?

For a glimpse into the deep gloom down where some of the actual, individual, 9099 Designation Numbers can be found, furtively scurrying to and fro within the dark hidden recesses of their native habitat, a rare and unusual sight that few human eyes have ever beheld.

The cables come up vertically from inside the bowels of the Pad (through a concrete tunnel starting from inside of the Pad Terminal Connection Room, if you must know), into the base of the 9099 Building, feed straight up from there until they reach a pivoting "cable ladder" (that's what it's called on the drawings) which is attached on its front side to the back side of the Dolly part of the Dolly (does that even make any sense?) with a fairly-substantial hinged connecting link, at which point they drape themselves up and over the curved top end of that "cable ladder" and then further drape themselves down and into the back end of the actual little 'cart' part of the Dolly mechanism, and from there, kind of drape back up a little as they extend to the back side of the front face of the Dolly, where all the connectors for the patch-cables are located.

What a mess! Structural people give Electrical people some "looks" a lot of times, and this kind of stuff is one of the reasons why. You can call the installations that the electrical trades construct a lot of different things, but one of the things you can not call them, is elegant.

Nope. Can't do it.

Even when it's all lined up, neat and orderly, dress right dress, it's still a bunch of goddamned snakes that live inside the ugliest cage in the whole zoo.

So anyway, the forward-pivoting movement of the cable ladder, plus all that "drape" in the cables, gives them the extra length they're going to need in order for the Dolly to be rolled 5'-4" forward (it's on the drawing) to where it's now close enough to the side of the MLP to allow the electrical techs to go fetch their Big-Box-O-Cables, take all zillion and one patch-cables out of it, and then... careful now... connect each and every one of them, correctly, to the Dolly, and then again on their other ends, to the MLP.

Phew!

It ain't pretty, but it does at least work, and once it's all nice and put together, it's pretty robust, too.

Here's the result, looking north, from a position south of the southernmost Dolly/Interface, so you can see the whole schmutz.

And here they are here, connecting things to the MLP, just so you can kind of get an idea of what they're dealing with at the 9099 Interface.

But if we give everything the consideration it's due, even here, in The Heart of Darkness, we can understand all of this. In the photograph, we can see that the area where the Dollys (none of which are actually visible in the photograph) are stowed in their retracted positions is quite dark (excepting the lighter shades of all the junky stuff intervening in front of the darkness of course), and that's because the roll-up doors (which are called "Steel Curtains" or "Roll Up Steel Curtains" or even "Rolling Steel Curtains" on some of the Apollo drawings, using a nomenclature that fell out of use many decades ago) are all in their stowed, rolled-up, positions, and therefore are also not visible, and we find ourselves looking into the impenetrable lightless gloom of the interior of the 9099 Building instead.

And what, pray tell, is going on with all of that "junky stuff" in there? What is that stuff, anyway?

And we return to our Apollo drawing and discover...

Asbestos!

Everybody loves asbestos, right?

Right??

Well... maybe not so much, really.

But actually, back when Apollo was flying (or even just still getting built, or actually, even before that), everybody really did love asbestos.

They put it everywhere.

They even put it in cigarettes!!!

ArrrrrgggghhhhhhhiiiiiEEEEEEEEE!

God, I wish I was kidding, but I'm not.

I can just hear them talking to each other over at corporate. Up on the top floor of corporate, I might add.

"Say, whatta ya think we should put some asbestos in our cigarettes?"

"Wow, C.J., that's a great idea."

"Yeah... it is, isn't it? I mean... our tobacco's not really bad enough on its own, right? I mean... we can make it even worse, right? And the fools who smoke the stuff will think we're doing 'em a favor, by putting this great filter stuff, in the filters of their Kent Cigarettes, right? They're so easy to manipulate, right?"

"C.J., you're a genius. We'll get the production and marketing people on it right away. This one's going to be BIG, I can just tell."

And of course, the really frightening part is that these people were already aware of not only what tobacco was really doing, but they were also aware of what asbestos was doing.

And they suppressed every bit of it.

For as long as they humanly could.

And I can hear The Stupids telling each other, "Let's elect a guy who will run the country like a business. What a great idea! Business Guys really know how to get it done! Good thing we're so smart and know who the right people are, huh?"

Pshit.

Ok, where were we?

Oh yeah, out on the launch pad. Trying to figure out "junky stuff" that is somehow associated with asbestos.

This whole interface area, where some serious electrical cabling was getting manually connected and disconnected, outdoors I might add, on a regular and routine basis, constituted more than just a little bit of a potential fire hazard.

"Be careful hooking that cable up there, Lou."

KaPOW!

And of course, working in the other direction, a little protection for all these cables from external things might not be such a bad idea, either.

If seagull was to fly by overhead, and drop a lit cigarette (Seagulls aren't smart, right? You would expect a seagull to be smoking, right?) down onto the cables, that wouldn't do the flammable rubber insulation on those things any good, would it?

And once upon a time, asbestos, in fabric form, was just about the best thing you could get, for fireproofing stuff. Ignoring all that tedious mesothelioma mumbo jumbo, of course.

And so, in between each of the four Dollys, and on top of 'em too, they very sensibly decided to kind of maybe hold down that whole fire-hazard thing, and to do that, they installed Folding Asbestos Curtains.

Observe.

And it turns out that the "junky stuff" we're seeing in the Dolly Area is the scissors-gate frameworks which the Asbestos Curtains were hung upon.

We've already met scissors-gate stuff in the form of the doors on Elevator 2, which the Astronauts used for access to and from their Apollo Mobile Launcher, and quite nearby, over here on the 9099 Building, we get more of the same, except this time it's not a door, but instead is something that can be extended out and back, something that can be folded back when it's not in use, and when we'd like to get it out of the way of our Saturn V's exhaust plume so as we won't have to keep looking for it in the next county over, after every launch, and so they went with this stuff, and there it sits, pretty (or ugly) as you please.

As for the actual Asbestos Curtains themselves, I have no idea. Neatly-folded and placed inside of a purpose-built storage box somewhere in there, most likely. Or maybe they'd already gotten wise to the stuff and had the guys in the hazmat suits take 'em away and get rid of 'em. I do not know. But. Back when I took my photograph, the whole "Asbestos" thing had not quite, not to the point of getting proper action, anyway, kicked fully into gear.

The ironworkers were still using asbestos welding blankets, and the change to fiberglass welding blankets only started up just a very short while later, and I distinctly remember every single one of those people being very pissed off about it, because fiberglass welding blankets were a laughably inadequate replacement for the asbestos ones, for the purposes of containing welding slag, which would, and did go right through them often enough, damaging whatever it landed on, and nobody was happy with that, and it was a Big Deal, and more than just a few ironworkers stealthily squirreled their asbestos welding blankets away in hidden places, and attempted to use them when they could, but those things were a kind of very pale gray, near enough to white, and the fiberglass ones were a kind of orange color, and you could spot the difference from a mile away, and the Contracting Officer wasn't having it anymore, and...